Organized by the Museum Lapidarium, Thursday 6 October 2016, Contemporary Art Gallery Miodrag Dado Đurić (National Museum of Montenegro), held the opening of the exhibition “Ivan Picelj: 1951. – 2011.”

The exhibition presents more than 50 Picelj’s works, part of the archive material and film clips. Most of the artworks are borrowed from the holdings of the archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, Modern Gallery in Zagreb, the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rijeka and from private collections. Exhibition catalog: text author is curator of the exhibition dr. sc. Jerica Ziherl and the preface wrote Brane Kovič, a prominent Slovenian art historian and art critic.

The exhibition will be open until 6 November 2016.

After Cetinje, the exhibition “Ivan Picelj: 1951. – 2011.” will be presented at the Art Gallery Dubrovnik in Dubrovnik, from 10 November to 11 December 2016.

The exhibition is co-financed by the Ministry of Culture, the City of Zagreb, the City of Pula-Pola, the City of Dubrovnik and the National Museum of Montenegro. Thanks to Croatian Radio and Television on the transfer of the documentary film “new tendencies Zagreb 1961-1973”, HRT Zagreb, 2010, 60′.

Brane Kovič: “Ivan Picelj Between Utopia and Creative Invention”

The role and importance of Ivan Picelj as a painter, printmaker, sculptor and graphic designer in post-war European art are well known and confirmed by numerous exhibitions in the country and abroad, many significant awards and recognitions, as well as critical reviews of his rich oeuvre in catalogues, monographs, specialized publications and various articles in dailies and periodicals. His creative achievements were often followed and thoroughly analyzed by the most reputable connoisseurs of the art scene over the past decades and we can reliably confirm that he was the only artist from the territory of former Yugoslavia who commanded global attention and respect albeit he never permanently moved to a world metropolis. His home and his studio were in his native Croatia, or more precisely in Zagreb; his second spiritual and creative home was Paris; while he was also a welcome and appreciated guest in Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Great Britain, USA, Latin America, Israel and many other countries. He had friends all over the world, not only professional colleagues and like-minded persons, gallerists and art collectors but also writers, musicians, photographers, people from the theatre and film world, the world of fashion and a number of other fields primarily characterized by inventiveness, imagination, creative thinking and intellectual curiosity. With his unique charm, politeness and sparkle, this elegant cosmopolite, fluent in several European languages, established contacts and made new and new acquaintances (which often turned into sincere and deep friendships) wherever he went or was invited.

I started familiarizing myself with Picelj’s work as a wannabe student of art history at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Ljubljana, since among modern and contemporary art trends I was particularly attracted to constructed art with its specific aesthetic and formal variations. Together with Aleksandar Srnec and Božidar Rašica, Picelj was a co-founder of the legendary EXAT 51 group, which organized its first exhibition in 1952 in Picelj’s Zagreb flat; he was an eminent representative of these artistic tendencies and at the same time one of the pioneers of abstract art in the entire territory of the former joint state, that is in the whole of what was then the eastern part of the political space split into two blocs. In 1959 began Picelj’s collaboration with the Denise René Gallery in Paris (where he exhibited his works for the first time with Srnec and Vojin Bakić, sculptor), lasting and fruitful for the artist as well as expanding his circle of like-minded artists, critics and supporters. Anyway, from that moment things developed rapidly: in connection with the artists gathered around this renowned dealer, tireless organizer and convincing ambassador of op-art as well as programmed and kinetic art appeared the ideas that culminated in the foundation of the New Tendencies movement, one of the most original and most penetrating artistic phenomena in the 1960s. The concept finally crystallized after Picelj’s encounter with Almir Mavignier, a Brazilian artist and Albers’ student in Ulm, coming to realization in 1961 with the first exhibition in the Zagreb Gallery of Contemporary Art, run by Božo Bek at that time. In the following twelve years another four exhibitions were successively organized summarizing and unifying for that time undoubtedly the most advanced research aspirations of the artists and theoreticians who understood the significance of the development of science and technology for modern society and at the same time firmly believed that this context also included art based on rational principles and high ethical norms. Certain artists recognized “the latest avant-garde” in these currents (e.g. Lea Vergine, the author of the accompanying monograph and the curator of the exhibition with the same title held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan from the beginning of November 1983 to the end of February 1984, who particularly emphasized the period between 1953 and 1963, without neglecting the unavoidable historical reference from the first decades of the 20th century). Notably, it was quite clear that abstract artistic expressions on the opposite pole (Art Informel, lyrical and gestural abstraction), especially in Europe, had been exhausted, had turned into repetitive manner and lost its former aesthetical value. On the other hand, on both sides of the Atlantic, as a kind of “alternative”, various figural, in fact conservative and for many dealers and art collectors more attractive trends and production practices developed (pop art, new figuration, hyperrealism, photorealism and others), whose derivatives led to a marked eclecticism which reached its peak after 1980 as a predominant feature of so-called postmodernism.

During his membership in EXAT 51 and in the period of his active involvement in the New Tendencies movement, Ivan Picelj developed his own visual language on the tradition of rational concepts of Russian constructivists, Bauhaus and De Stijl, the art phenomena which strived to erase the borders between “pure” and applied art and which therefore considered that graphic and industrial design should be treated the same way t as painting and graphic art. If dealing with the classic art practices in the field of geometric abstraction is largely internalized, self-referential and self-reflexive, in the sense that form and content on the level of visual effect are truly equal, design as the fulfilment of precisely defined tasks implies functionality and communication. Picelj began transferring his experience and exceptional knowledge about the most updated aspects of visual thinking at the international level into designer practice already before EXAT 51 was founded, and he gradually improved his sign and typographical language, widening the territory of its applications. The silkscreen technique chosen for the realization of his art prints, turned out to be exceptional also for designing visual messages, and in typographical solutions among varieties of typeface or fonts he very early decided to use Helvetica, introduced in designers’ options in 1956. The synchronized coexistence of Picelj’s art and design achievements which stemmed from the interaction of programmed, kinetic and initial computer i.e. informatics structures ensured to the artist numerous commissions abroad, especially in France, where he frequently designed posters and various publications for the most eminent cultural institutions and publishing houses. In the context of the continuity of Bauhaus thinking and the postulates of Ulm School, Picelj’s acuteness and the impact of his works are more understandable since the principles of order and neatness represented a truly refreshing contrast to the Paris School, the anarchist gestural abstraction and innermost restraint, which were to a large extent a limiting factor for the domestic art scene. How revolutionary were the achievements of suprematism, constructivism and neo-plasticism in the history of modern art, Picelj and his fellow artists kept repeating even when 20th century was moving towards it’s end and when European and American galleries were flooded by artefacts of neo-figural provenance with more or less evident neo-expressionist touch, but in fact extremely reactionary derivatives and remakes of movements that were avant-garde, socially engaged and politically provocative at their inception, while with partly modernized iconography and superficiality of execution the great majority of that production seemed highly unconvincing, forcedly anarchic and frequently cheap almost to the extent of being vulgar, even kitsch. All this outburst of arbitrary image-production was labelled by Getulio Alviani in a mischievous manner as “il mondo del casino”, a wretched caricature of avant-garde ethics and the aspirations of those artists who sincerely strived to achieve the principles they believed in and wanted to share with the emancipated, contemplative audience ready to resist the tricks and manipulations of consumerism characterized by the incessant hunger for novelties, in most cases fake or only apparent.

The typological model which soon became an unequivocal distinctive sign of Picelj’s polyvalent creation was strongly confirmed by his entrance into the ground of exploring the programmed variations and modifications of primary geometric forms. One of the first manifestations of this decision of the artist was undoubtedly the print portofolio Oeuvre programmée No. 1, published in 1966 by the Denise René Gallery in Paris, and can be regarded as the beginning of the thematic range materialized in the following years and decades in new editions, well-deliberated and supremely executed silkscreen portofolios, each of them being a completed whole, while at the same time each print is a perfect visual entity. The following were created in a chronological order: Cyclophoria (Paris, 1971), Géometrie élémentaire (Bergamo, 1973), Connexion (Zagreb, 19791980), Remember (Malevich, Mondrian, Rodchenko) (Paris, 19821984) and three different editions of Variations (Zagreb, 1992, 1994, 2002); the last one, entitled Ulm variations, was published in 2006 by the International Centre of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana. It can be considered a specific deuteronomium of Picelj’s law, formal and ideological paradigm established by persistent experimentation as a conditio sine qua non for discovering new things. The title of the series of eight silkscreens was not selected by accident: established in 1953 and active until 1968, the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm gave life to and upgraded the aspirations and orientation of Weimar Bauhaus, and its professors, led by the Rector Max Bill, chose research of the relation between artistic imagination and scientific thinking on the rational base as the starting point for their teaching. Rationalism as a methodological dispositive in the newer philosophy is inseparably connected with the writings and deliberations of René Descartes, who spent several months of his rich life, marked by numerous travels and changes of dwellings, in this German town. The brilliant series of chromatically ingenious compositions of orthogonal structure, composed of four units with black and white contours can be understood as Picelj’s graphic homage to the artistic visions of Ulm School and Descartes’ cogito, in the continuity of the concept of the referent triptych exposed in the portofolio Remember. The artist focused on the always open question of logical combinatorics, with the assumption that he had at his disposal a particular geometric form and the primary colours of chromatic spectre. The articulation of the relation between the forms and colours is done according to the mathematical model selected in advance, which dictates multiplication or reduction of both structural components, which means geometric forms within the entire picture surface and the chromatic elements and their interferences. However, despite this strict determination of articulation procedure, ultimately Picelj’s solutions in their phenomenological appearance make visually attractive statements that are always upsetting for the eyes and the spirit. Namely, the precisely defined form is not a priori limiting, quite the opposite, it is precisely within it that the artist’s subjective invention is revealed in its full strength and suggestivity, and at the same time this confirms the fact that none of the formal structures are accidental, but they act as an obligatory content. In this sense, Picelj’s Ulm variations are another original visualisation of a particular mental concept which by its openness presents the coexistence of spiritual and sensual understanding of the universe without pleonasms and rhetorical exhibitionism. The evoking of memories is manifested here as the moment of revelation of the values which proved to be utopian in practice and maybe precisely for this reason so inspiring, not only in artistic terms, but also as an existential impetus and fusing of the creative aspirations with the deepest personal convictions. From this viewpoint, Picelj’s artistic production and his human position are inseparable, and fused into an ideal unity of a system through which we interpret his images, and turn his statements into mental pictures. In the empirical coordinates of the constructive visual thinking, each time his intimate dedication to the visionary paradigm of order and logic glows again, which we all imagine in a world going mad, but which only the rare ones can articulate in suggestive syntagmatic formulations. Picelj was surely one of them.

I had the honour of meeting Ivan Picelj in person in Zagreb in November 1981, on the occasion of opening the 3rd ZGRAF, a great international exhibition of graphic design accompanied by a series of other events. I was introduced to him by Ranko Novak, originally from Zagreb, who built his career as a designer in Slovenia, or more precisely in Ljubljana, where he practically became a legend around 1975. ZGRAF left an imprint on my memory also because of the participation of the cult designer group Grapus, led by Pierre Bernard, and Picelj and me immediately found a common language with the group’s members. The intensive daily schedule of events unavoidably extended into pleasant evening gatherings during which professional debates were blended with cheerful chitchat about what we all loved (among the people I spoke with, it is with special warmth that I remember the late Antoaneta Pasinović Pasa). This association was the beginning of a long, sincere and deep friendship with Jean (Žan), as Picelj was called by all the people close to him, and this friendship lasted up until his sudden death five years ago. I used to visit him in Zagreb, we would meet in Ljubljana, and we had the best time in Paris, which was practically an ideal environment for our areas of work (not to mention the other charms and temptations of the French capital). Both of us had our own friends, colleagues and acquaintances there who, one after the other, became our mutual friends; we had our favourite cafes and restaurants, places of memories and inspiring discoveries… Jean also introduced me to Dinko Štambak, a great Croatian intellectual and author from the first generation of the French post-war scholarship holders – he had the history of Paris and the artistic pulse of the metropolis at his fingertips, and the “afternoon office” in La Chope cafe at Place de la Contrescarpe in the 5th arrondissement; then, he introduced me to Radovan Ivšić and Annie LeBrun, whom I liked to meet even when I was in Paris on my own; he used to take me to the studios of Jesus Rafael Soto and Yaacov Agam, we visited Joel Stein and the photographer Peter Knapp, and it was with special joy that we made a visit to Carlos Cruz-Diez, an extremely warm and hospitable person and a brilliant artist that I occasionally go out with even today; finally, Denise René left a very strong impression on me – Picelj’s gallerist of many years, a great lady of the world renown in her profession with whom I had the honour of doing two long interviews for the Slovenian media. Whenever I stopped by her gallery without Jean – whether the one on Saint-Germain Boulevard or the one in the Marais or in her exhibition space at the art fair in Basel and FIAC in Paris straight after the greeting she unfailingly asked: “Vous avez vu Picelj?” (“Have you seen Picelj?”) and I liked telling her about his work, plans and our joint adventures. When his friends from abroad came to visit him in Zagreb and decided to make a visit to Ljubljana too, he would usually give me a call and ask me to wait for them and take them on a tour. I used to do the same as well. For example, many years ago, during the time of former Yugoslavia, I met the American-Israeli gallerist and art collector Horace Richter at the Art Basel and when I told him where I came from, he immediately asked me if I knew Picelj and how things were with him. Then we walked down to the nearest telephone booth and dialled Picelj’s number and they were both thrilled to talk to each other. Horace decided to go to Ljubljana with me and then to Zagreb to see Picelj again after so many years. There were a great many similar encounters, which only confirmed Jean’s cosmopolitism and international reputation earned through his art work.

In addition to the similar views on art and various life situations, from the very first day our friendship gained a special dimension through the francophonia and francophilia we cherished and reinforced whenever possible. During our conversations, often in the company of our mutual friend and artistic companion Getulio Alviani, various topics of the aporias of contemporary artistic practices and labyrinths of their performances came one after the other, of exhibitions and literary news, of the clear and well-argued positions, of delusions and cheap rhetoric of their authors and so on. On several occasions he wanted to take me by surprise with a book he had just received from Paris and which had delighted him, and when I told him that I had already read it, he just laughed, waved his hand and we had a new topic to discuss again. Our last direct contact was marked by the thought of a new joint project, the preparation of a monograph I was supposed to write the text for. He was first attracted by the idea, and then he nearly gave it up, saying he didn’t need that, it required much work that he wasn’t keen on doing. Eventually he agreed to do the work but on condition that this was not an ordinary monograph with a classical critical or art historical text and a series of reproductions, but an entertaining, funny book in which his work and his life path would be intertwined with anecdotes, adventures, comments; in brief, this was to be a look at his art as part of his everyday life, his thoughts, memories and feelings. This was to be a book reflecting his entire approach to the field of his creation, from painting, printmaking, objects and design to his beliefs and knowledge, experience and wisdom with which he accepted the reality he lived. However, Jean’s sudden death prevented the realization of this project; but even if someone in future became keen on it, without the artist’s living presence, the monograph would certainly not be as Picelj wished it to be and imagined it.

With reference to our thirty years long friendship, at the end I would like to mention a small but important detail: a habit we carefully nurtured and never gave up. Notably, from our relatively frequent trips, we regularly sent postcards, not text messages or e-mails but ordinary postcards written in fountain pen, which by rule began with Cher ami… I sent him the last one from Madrid on a Saturday in February 2011, informing him that I had seen two great exhibitions: Polish constructivism at the Círculo de Bellas Artes and geometric abstraction of Latin America at the Juan March Foundation, where many of his acquaintances and colleagues from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela and other countries were showing their works. Unfortunately, he never read it: when the postcard arrived at his home address, Jean was no longer among us.

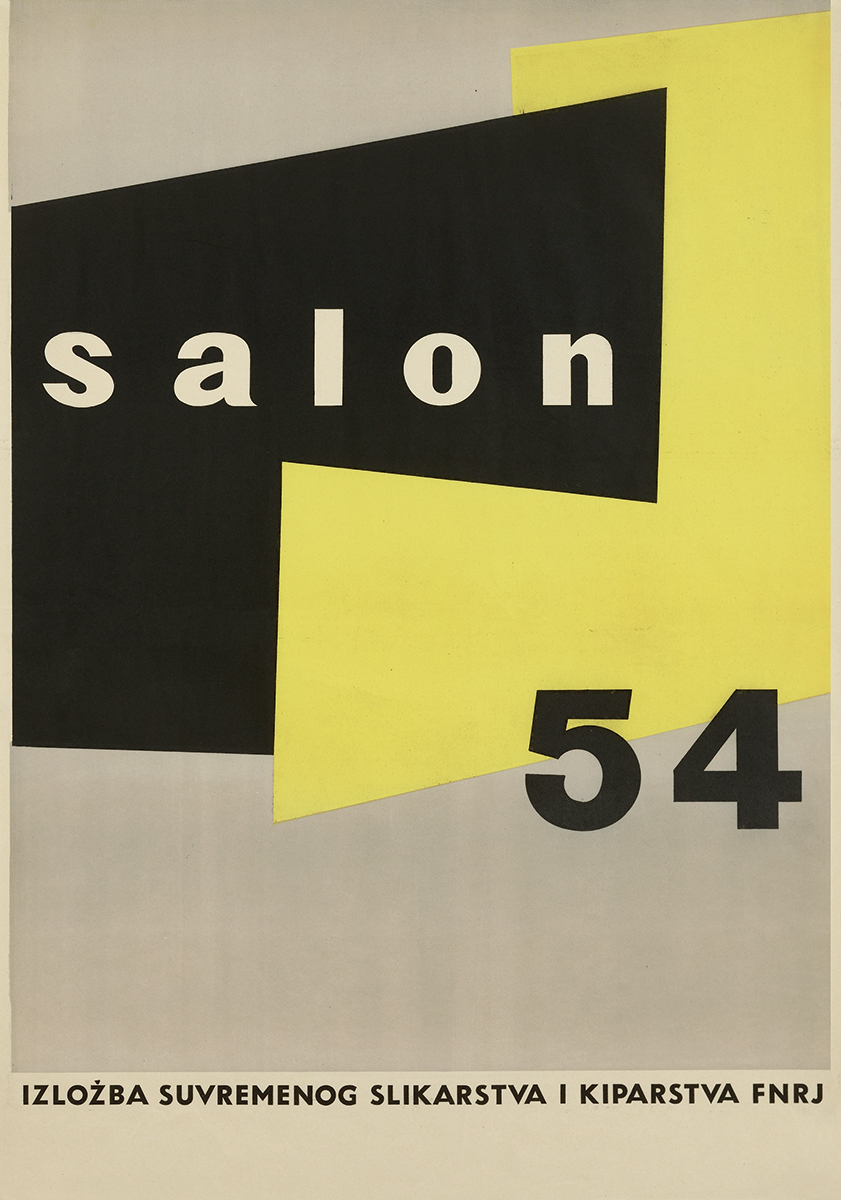

Poster for the Exhibition Salon 54, 1954.

litography, 1000 x 700 mm

Courtesy: Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rijeka

Photo by Goran Vranić