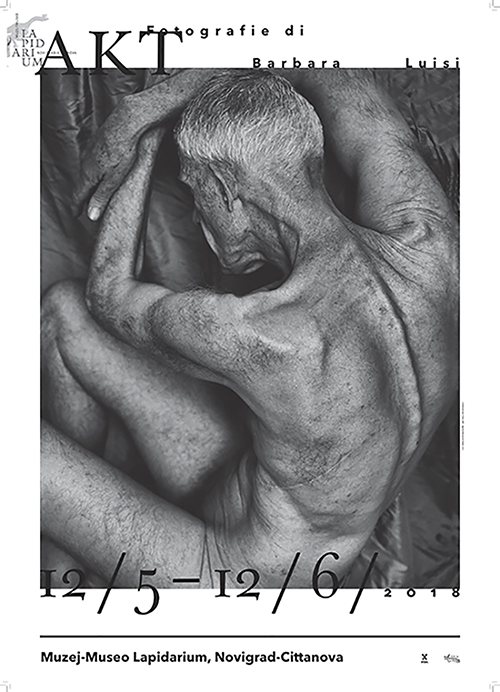

AKT. Fotografie di Barbara Luisi

Exhibition opening: 8 p.m.

Curator: Manuela De Leonardis

12/5 – 12/6/2018; Museum Lapidarium

The surface of the sea, slightly ruffled, never perfectly even—like the bark of the trees, tells of an eternal story, a cyclical story that goes back to the beginning of the world. The human body has a different cartography. The temporal limit marks the border between moments, the fragment of a present projected into the utopia of immortality, even more so, when the body is returned to an atavistic nudity. Then, it takes on a stronger symbolic and metaphorical valence.

Likewise in the language of photography, heir of previous forms of art, there is appropriation—of myth at first—while experimenting with autonomous variations. Biblical nudity, in the passage from pre- to post- original sin, takes one into the process of transgression, shame, and punishment, but also of awareness. To face the idea of the limit leads to growth, which, in a way is like being re-born.

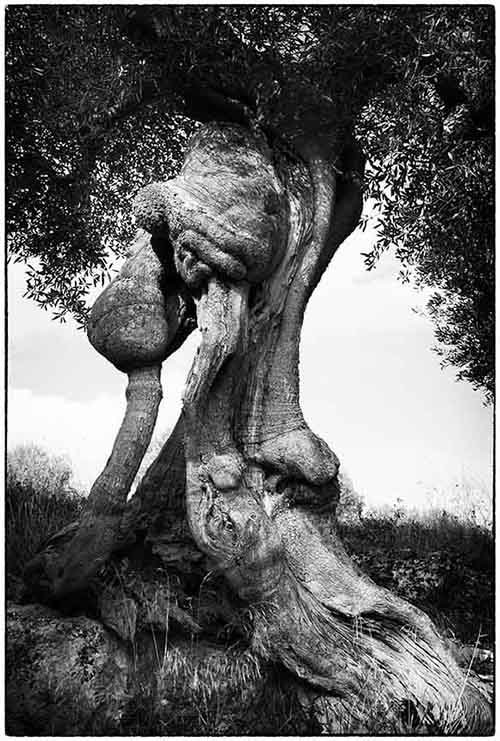

In Barbara Luisi’s modality of treating the nude, there is a very strong connection with nature. The skin, the knottiness, the apparent fragility are rich of cross-references to the living beings of the animal and plant world. Olive trees especially are those thousand-year-old bodies that her trained eye captures in the land of Apulia. The photographer compares now the carefree agility of youth, now the heaviness of declining bodies to bodies of all ages and races—female and male ——who she invites to pose for her. Beauty is the goal of the path. A beauty that contains the dissonant element, as with Japanese aesthetic, according to which harmony cannot but spring from elements that swing between two opposites of an implicit duality, as well as dignity.

low res Barbara Luisi, Ulivo 20, 2016.; Courtesy of the artist

There is attractiveness even in those bodies that contemporary society penalizes because of their age, and it is a powerful attractiveness. Of the young ones, instead, Luisi seizes the thrill that makes even the innermost moods emerge through the skin, related to the modesty of the first time when they let themselves be captured unmasked by the indiscreet eye of the camera.

As with trees, individuals pose in groups of two, three, or four. “Trees need a social life,” says Barbara Luisi, “the young ones, planted next to the older ones, can give them vitality through their roots.”

Bodies that intertwine giving way to the steps of a virtual dance, fast-paced dialogues of gazes: the series Fragility (2013-2015) as well Akt – ageless beauty (2016-2017) defines the meaning of intimacy by allowing traces of eroticism to surface without any sense of provocation. Often hands and feet are the focus. Photography is invited to share an intimacy that is born out of the improvisatory quality of the models’ gestures (they are not professional), rather than from the exigencies of the photographic set, from their whispered words, and from the way they move in the darkness of her studio, “each one expressing feelings of being trapped inside themselves.” A perceivable unconditional freedom, enters in the composition of the image. Fragility is understood as something other than a potentially labile psychological condition, in its potential as gift, as a secret to protect.

The intimacy that draws Luisi close to her subject, allowing her to venture into the mystery of their integral nude, brings us back to our times and reminds us of the intimacy between Flor Garduño and his “models-accomplices” portrayed in the small studio built with adobe next to the kitchen in his house of Tepoztlán in Mexico. Concerning the postures, if in Nude Nature one could recognize Edward Weston’s influence, the plastic construction of the sculptural bodies of Amanda, Christa, Eric and Mat (it is significant for the photographer that the images in the series Fragility carries the models’ names) defined within a neutral space in her studiofinds a citation in the majestic nudes by Bill Brandt and Irving Penn, and in the naturalness that conveys the physical and sexual energy. Certainly, images such as the one in which Amanda is crouched down, with her long, loose hair that holds the forms of her adolescent body, remind us of Francesca Woodman’s introspective gaze.

However, the avowed mentor is Eikoh Hosoe. Differently from him, Barbara Luisi does not take to their extreme the contrasts between white and black to affirm the strong need for freedom, which for the Japanese photographer corresponds to the tumultuous Sixties (which corresponded for him to the exuberance of his youth). Rather it is an interpretation of the real by subtracting elements; just as it happens in music, in which numerous possibilities find expression through the combination of only seven notes. As Barbara Luisi explains, “To find differences with a few means brings to a heightened focus and a more intense emotional approach.”

Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses (1961-62), considered Yukio Mishima’s testament, of Hosoe’s photographic work is the one that has inspired her the most, included the book form that is a work of art in itself. The portrait of the writer Mishima with a rose in his mouth is the first photograph one meets in her studio in New York, next to a portrait by Nadar, and a shot by Henri Cartier-Bresson, the theorist of the decisive moment, taken with his Leica. It is a Leica M6 that Barbara Luisi buys with the first earnings as a violinist, thus entering a path in which music and photography will always be intertwined.

Later on, she attended a workshop given by the Japanese master at the Palm Spring Photo Festival in 2007, where she learns the spontaneity of his direct approach to the subject. Luisi recalls “observing him while he was photographing nudes. Not being an American, he was not concerned with keeping himself at a distance from the nude bodies. He worked like a sculptor. It was still immersed in the ethos of the flower power movement and the workshop was designed like a happening. For me it was very surprising, especially because of his advanced age and his precarious health. He held the workshop in the desert and in his house there: at the end we were all naked included his collaborators, except for him, photographing each other. It was not the one-directional teaching from master to students rather it sprung from the need to do something collectively. You could breath that idea of freedom and liberation that had circulated in the Sixties.”

Rigor, quality, and perfection are the elements driving Barbara Luisi’s method, in which the methodical collector’s approach plays an important role: her photographic collection includes rare works and books, first editions of the great masters, such as Eugène Atget, Frida Kahlo, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, alongside the already mentioned Nadar, Hosoe, and Cartier Bresson. Of her working process she says, “at least a few years go by between the first shots and the idea, then starts the real research work. I am a collector of my own ideas, which I keep in the dark until the right moment comes to develop them.”

Suspension, tempo, movement: terms that belong to the language of music, yet they find a correspondence in the methodological approach to photography. They translate into long-term projects, connected with each other, in which she exercises an almost obsessive control over the result, both at the stage of the shooting and of the dark room.

She further explains: “My work is also connected to travels, therefore it implies the possibility of being able to add something that I see in a given situation, and that, perhaps, I had never noticed before. Perhaps here too beats the collector’s heart. Certainly, when I take photos I am still a musician, because photography always involves a certain idea of sound and silence. Music is a necessity for me. To study violin requires daily practice, but in the very moment I play I can travel with my thoughts. At times, they are thoughts that influence my idea of photography, because imagination always includes a visual aspect. “As a photographer,” she concludes, “I do not have the right to modify the image I see, but I can enhance it with the rules that I have established for myself.”

– – –

Design by Oleg Šuran

The program is supported by The Italian Cultural Institute in Zagreb and City of Novigrad – Cittanova.